|

Margaret R. Miles, "Preface," Carnal Knowing: Female Nakedness and Religious Meaning in the Christian West (Vintage 1989) xi-xv.

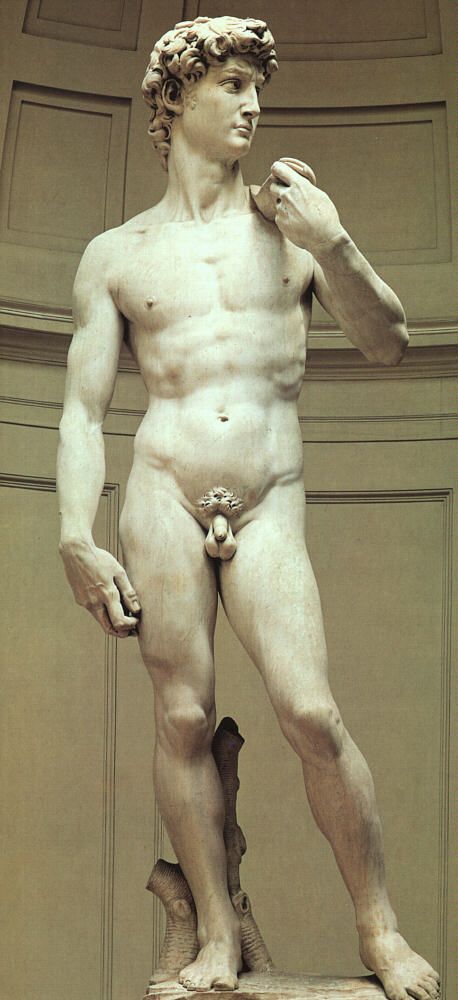

PREFACE Der Schatten der Vergangenheit liegt über dem Körper1 This book originated in my puzzlement over the bewildering array of meanings associated with naked bodies embedded in the recorded practices, texts, and visual images of communities in the Christian West. Naked bodies gathered meanings that ranged from innocence to shame, from vulnerability to culpability, and from present worthlessness to future bliss in the resurrection of the body. Julia Kristeva has stated that "significance is inherent in the human body," but little more can be said about what is signified until one examines the meanings of bodies in their particular religious and social contexts. The first theological meaning of nakedness in Christian tradition was the innocence, fragility, and vulnerability of human bodies in their initial creation. In visual images, the creation of Adam and Eve follows the Genesis account in depicting Adam's creation from the breath of God and the dust of the ground and Eve's creation from the side of the sleeping Adam. Narrations of the fall of the human race, however, focus on Eve and her initiative in sin. Paintings, mosaics, and bas reliefs, like commentaries on Genesis, reflect Ecclesiasticus 25:24: "From a woman sin had its beginning, and because of her we all die." The Fall resulted, scriptures say, in corporal punishment: Adam was condemned to hard physical labor, and Eve to laborious and painful childbearing. Nakedness in the state of sin represents the shame and pain associated with punishment. A more positive theological meaning of nakedness was captured by Jerome's famous statement, "nudus sequi nudum Christum" ("naked to follow a naked Christ"). This became the slogan of late classical and medieval ascetics who, identifying with the spiritual commitment of the martyrs of the early church, called themselves "daily martyrs." Stripping themselves of possessions, family, and familiar environment, they entered full-time training in the Christian life. Christian tradition incorporated the motif of the naked male body, used since antiquity to represent heroic physical strength, to symbolize the spiritual exercises of the ascetic "athletes. " Male nakedness represented spiritual discipline, physical control, the vigorous appropriation of a religious identity, and undistracted pursuit of an athletic crown (See Michelangelo’s David.).

Male nakedness symbolized religious commitment. Female nakedness, though it sometimes represented ascetic penitence, had a different role in the representational practices of the Christian West. Female nakedness received its symbolic representation in cultures that associated women with body, men with rationality, and (only) rationality with subjectivity. Eve's nakedness, described and painted in the "texts" that formed the interpretive lexicon of Christian tradition, represents religious meanings that range from innocence to sin, lust, and death. But it does not represent Eve as the subject of her experience. Other religious meanings cluster around naked bodies: in the thirteenth century, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux popularized the idea of nudity as symbolic imitation of Christ; it took a Saint Francis to act out this metaphor. Francis announced his betrothal to Lady Poverty by publicly stripping off his clothing and flinging it at the feet of his protesting father. Similarly, in the fourteenth-century mystical tradition founded by Meister Eckhart and carried to Martin Luther by Tauler and Suso, nudity received the less literal interpretation of the soul's divestment of cares, attachments, and ideas in order to expose the "core of the soul" where God is to be found. Ironically, the soul, departing from the body at death, was painted as a tiny, colorless naked body, carried to heaven in a napkin by angels. Negative meanings of nakedness were formulated more slowly in Christian tradition. Nakedness and sexuality or lust were seldom associated in patristic writings. At worst, nakedness was seen as weakness. Before the sixteenth century there were few suggestions that the specific content of original sin was sexual desire, and there is even less evidence of the idea that sex brought death to the human race. In chapter 5, however, we will examine a series of sixteenth-century visual images in which female nakedness is used to represent sex, sin, and death. Two different kinds of historical evidence will direct our exploration of social and religious meanings of female nakedness in the Christian West. The first part of the book will focus on religious practices—baptism, asceticism, and martyrdom—in which Christian women were naked, voluntarily or involuntarily, in public places; in the second part, textual and artistic representations of female nakedness will engage us. Public representations, I will contend, are closely connected to politics and social and sexual arrangements. Thus, although I will focus on texts and visual images, I will also seek to identify the most relevant features of their social contexts. Are questions about social location, institutional affiliation, and gender politics anachronistic? Will they result in misreadings of texts and visual images? Clearly, analysis of gender constructions calls for a disobedient reading, a reading that looks for the effect of the artist's or author's rhetorical or pictorial strategies rather than for the author's intended communication. The effect we must look for, however, is not that of the image or text on either a historical or a modem reader or spectator, but the ways in which gender constructions are embedded in communications so naturalistically that the author can count on them to move an argument, to persuade, or to seduce. Moreover, the abundance of literary treatments of the relative nature, capacities, and social roles of women and men throughout Western history indicates that these were far from indifferent matters in historical societies.2 Historical people did not develop an analysis of gender conditioning and its social effects. In the Christian West gender difference was thought to be biologically based, scripturally attested, God ordained, and unquestionable. Yet even though gender roles were considered "natural," men worried enough about the potential insubordination of the "inferior" sex that they spent enormous amounts of time and energy on rearticulating and reaffirming what women are and should remain. Because representations of female bodies were a vehicle for a complex communication, we need to explore the particular expressive content they carried.

NOTES 1. Barbara Duden, Geschichte unter der Haut: Ein Eisenacher Arzt und seine Patientinnen um 1730 (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1987), 172. 2. Although I usually avoid the emotionally charged word "patriarchy," it does accurately describe the male-designed and administered societies of the Christian West. Thus it is important to say at the outset what I mean by "patriarchy," whether I use the word itself or a synonymous phrase. I use the concept of patriarchy "thickly"; minimally, it is descriptive, indicating that Western Christian and post-Christian societies are and have been designed and administered by men. By "patriarchal," however, I also mean that the formal and informal institutions of these societies are designed to embody and support the agenda of male psyches. Freud described the psychological roots of patriarchal domination in the relationship of the male infant to the mother, especially in the dual and contradictory need of the infant, on the one hand, for recognition by the (m)other, and on the other hand, for independence from the (m)other. Classical psychoanalysis formulated individuation as a difficult and dangerous process of creating a self-other distinction, a development in which "merging was a dangerous form of undifferentiation, a sinking back into the sea of oneness." The infant's task, according to Freud, was to strive for omnipotence and control. The little girl, since she can grow up to be "like" the mother, need not, like the boy, struggle to "have," to possess, the mother. On the level of society, patriarchal institutions reflect the psychic agenda of the male infant-domination and control. See Jessica Benjamin, The Bonds of Love: Psychoanalysis, Feminism, and the Problem of Domination (New York: Pantheon, 1988), 81- 84. |

Both women and men engaged in the ascetic life; in

fact, women ascetics were esteemed more highly than men because of the extra burden under

which they labored, the "natural" weakness and susceptibility to temptation of

their sex. Women who practiced asceticism were called "male," an interpretation

of their efforts that women apparently accepted. For example, Perpetua, a nursing mother

at the time of her arrest and imprisonment in early third-century Carthage, dreamed of her

approaching martyrdom as an athletic contest. In her dream she was stripped of her

clothing by attendants and rubbed with oil in preparation for fighting a huge Egyptian

gladiator. As her garments were removed, Perpetua's body became a male body, the only body

in which she could imagine herself possessing the stamina, control, and strength necessary

for martyrdom.

Both women and men engaged in the ascetic life; in

fact, women ascetics were esteemed more highly than men because of the extra burden under

which they labored, the "natural" weakness and susceptibility to temptation of

their sex. Women who practiced asceticism were called "male," an interpretation

of their efforts that women apparently accepted. For example, Perpetua, a nursing mother

at the time of her arrest and imprisonment in early third-century Carthage, dreamed of her

approaching martyrdom as an athletic contest. In her dream she was stripped of her

clothing by attendants and rubbed with oil in preparation for fighting a huge Egyptian

gladiator. As her garments were removed, Perpetua's body became a male body, the only body

in which she could imagine herself possessing the stamina, control, and strength necessary

for martyrdom.