|

Margaret R. Miles, Carnal Knowing: Female Nakedness and Religious Meaning in the Christian West (Vintage. 1989) 169-185. NAKEDNESS, GENDER, AND RELIGIOUS MEANING Margaret R. Miles My body knows unheard-of songs.1 The female image in all its variations is the mythical consequence of women's exclusion from the making of art. It is arguable that, despite her ubiquitous presence, woman as such is largely absent from art. We are dealing with the sign "woman, " emptied of its original content and filled with masculine anxieties and desires.2 For me the real crux of chauvinism in art and history is that we as women have learned to see the world through men’s eyes, and learned to identify with men's struggles, and men don't have the vaguest notion of identifying with ours. One of the things I'm interested in is getting the male viewer to identify with my work, to open his eyes to a larger human experience.3 I have argued that female bodies, in the societies of the Christian West, have not represented women's subjectivity or sexuality but have, rather, been seen as a blank page on which multiple social meanings could be projected. My point throughout the book has not been to accuse men, who have created and administered the public sphere, of consciously and willfully creating religious practices in which women's socialization was reinforced rather than challenged. Nor do I claim that men consistently and purposely misrepresented women. Male artists and authors have sometimes represented women with sensitivity and empathy. Such theses would, in any case, be helplessly vulnerable to contrary opinions and counterinstances. My point, rather, is that because women have not enjoyed the conditions necessary for formulating the self-representations that could have informed collective male views of women, men have usually created representations of women out of their fears and fantasies. Men have figured "woman" as a frightening and fascinating creature whose anger and rejection could deprive them of gratification, delight, and, ultimately, of life and salvation. The damage of such unlimited projection has been felt by Western communities as a whole; issues surrounding representations of women are not "women's issues," but common concerns. "Political power entails the power of self-description."4 Perhaps the most accurate test of whether a social group has political power is to ask whether that group enjoys the power of self-representation. People who do not represent themselves live under conditions in which their subjective lives—their feelings, concerns, and struggles—are marginalized from public interest; they also live in constant danger of misrepresentation. If women have suffered the effects of a misogyny deeply embedded in the representational practices of the Christian West, can we envision the possibility of more equitable public images of women? Let us approach this question by considering further the conditions needed for representation. First, adequate representation of women must be self-representation. This is not to deny that one can learn something from "seeing ourselves as others see us." It is, nevertheless, arguable that, in societies that have represented women rather than providing conditions for their self-representation, women cannot begin by paying further attention to collective male representations of women. Since all women introject, to a greater or lesser degree, public representations of women, however, it is important to analyze what those representations circulate as the truth about women in order to understand some of the components of women's subjectivity. We do see ourselves as others see us. "In contemporary patriarchal culture Sandra Bartky writes, a panoptical male connoisseur resides within the consciousness of most women."5 Self-representation, then, will require both identification of the public images that have become women’s self images and the search for alternatives. Obviously, women's public representation by women cannot merely reverse men’s representations of women by using the male body to signify female desire, sexuality, and power. Secondly, the work of self-representation must occur in public, in the institutions and arenas in which the discourse that both reflects and shapes society takes place. Women must begin to gather the institutional power necessary to correct the male concerns and styles of interaction that have characterized public affairs. Until recently, the isolation of women from public engagement resulted in the privatization of women's talents and energies. Excluded from public discourse, most women legitimately felt reluctant to accept responsibility for society and politics and concentrated their attention on their families. As we have seen, concerted rhetorical and pictorial campaigns have, at various times and places in the Christian West, encouraged—if not compelled—them to do so. Limiting public power to male leadership has meant not only that women were deprived of public roles, but also that societies have suffered the loss of the contribution women might have made. If women are to achieve a different public representation than that of the male collective, we must develop a power base of leadership positions in public institutions. But we must also imagine and construct a different dynamic relationship between representation and power. Collective, public male power has tended to accumulate and congeal in relatively small power elites. Collective female power must be maintained and revised in continuous circulation; it must resist coagulation. Women's power, if it is not to reproduce the structure and dynamics of male power, must be understood as the mutual empowerment of people previously disempowered—ethnic, class, and age groups—and not as power over others. Women's power must be redistributed among people previously excluded from power as quickly as it is gathered. Instead of being represented as "other" or alien, these misrepresented people can use self-representation as an important strategy for maintaining power in suspension and circulation. Self-representation requires power, but it is also an instrument for producing empowerment. The third requirement for adequate representation of women is the construction of a collective voice. Individual perspectives, valuable as they are within a female collective, cannot command public attention sufficiently to make a difference in politics, the media, public institutions, or social and sexual relationships. If women are to escape public categorization under the rubrics of standardized female figures, a collective female voice that parallels and challenges the one-sidedness of the collective male voice will be necessary. "Collective voice" does not, however, imply that all women must agree on priorities, theory, or agenda. Diversity, particularity, and the disagreements they inevitably create are especially important to maintain and encourage—and even to find essential and delightful—within a female collective voice. "Unity," the ancient slogan of patriarchal order, is not the hidden agenda of

collective voice. Unanimity, even though it has been a goal rather than an achievement of

male collectives, has yielded representations of women that are amazingly constant over

two millennia and across a broad geographical area—"woman," the object of

male fear and longing, who, in revealing her body, is said to have revealed

"herself" Collective voice is also central to the process by which women can move toward self-representation. Only a collective voice contains the resources and support necessary for self-criticism and self-correction; individuals in isolation, or even in small groups, cannot consistently identify the myriad ways by which women serve societies without a critical examination of the effects of their support. Women's collective self-representation in the public sphere ultimately has the task and responsibility of deciding both what is to be said about women as women and creating the imagery and language to say it. The task, no doubt, is enormous. But it is already launched. In courts of law, work places, churches, public media, and academic discourse, the process of achieving the conditions for women's collective self-representation has been going on for at least a century, and with gathering momentum for several decades. The question is not whether women can and should represent themselves but how, at any particular moment, this can most fruitfully be accomplished. An accurate analysis of the present public situation, then, is preliminary to any determination of what kinds of self-representations will both formulate women's self-understandings and effectively challenge and change the public sphere. What characterizes women's present position in late-twentieth-century North American public culture? The anthropologist Bryan Turner has argued that, although most feminists still use the term, "patriarchy" no longer adequately describes the dominant culture of Western Europe and North America. The notion of patriarchal power, he says, "cannot be uncoupled from the existence of the patriarchal household and . . . the development of capitalist society, by destroying the traditional household, undermines traditional patriarchy."7 Turner characterizes patriarchy as the existence of (1) a legal system that legislates the subjugation of women as well as their economic exploitation, (2) political authority based on the use of the father's role in the patriarchal family as a model for divine-right absolutism, and (3) an ideology of mate superiority. Though women, he acknowledges, "still experience second-class citizenship, closure from elite professional positions, everyday sexism and petty discrimination," he maintains that "they also have much of the legal, political and ideological machinery by which that discrimination can be successfully challenged." As an ideology, then, "patriarchy is a defensive reaction in a society where marriage and the marriage contract no longer give [men] dominance in the household or in the market."8 As an "objective social structure which is maintained and constituted by a complex system of legal regulations, political organization and economic arrangements," patriarchy, Turner concludes, no longer exists in the Western world.9 Turner calls for a "new conceptualization of the position of women," a condition he labels "patrism." Using race relations theory as a parallel analysis of oppression, he distinguishes between sexism as a "collection of prejudicial attitudes" and sexism as a "social system in which certain social groups are suppressed and exploited through the operation of the market, political structures, and the law."10 He notes:

Turner's critique of feminists' use of the term "patriarchy" without definition of its content is a plea for theoretical precision. Wrong or inadequate theory is theory that doesn't work—that doesn't illuminate and that doesn't point the way to effective action. His proposal for the term "patrism" as a more accurate designation of the contemporary situation also has the advantage of recognizing that the women's movement, coupled with the dramatic decrease in the hegemony of the nuclear family, the "rise of individualistic values, the transformation of traditional authority, and the disenchantment of religious values,"12 has made substantial advances in dismantling patriarchy. The concept of "patrism," Turner claims, both defines the contemporary situation more accurately and reveals more pointedly the exact nature of the stresses involved in society's transition away from "patriarchy." Despite the advantages of his theory, there are, I think, fundamental problems with Turner's analysis. While it would perhaps be encouraging to believe that patriarchy is in a state of collapse and that it presently occupies a "contracting power position," it is, in fact, not the case that equal distribution of social and institutional power exists among women and men. As long as the top administrative positions in social, political, legal, and ecclesiastical institutions are dominated by men, one cannot speak of "an institutional shrinkage of patriarchy." Furthermore, women who are "equipped with a powerful ideological critique of traditional patriarchy" are limited largely but not entirely to educated middle-class white women. This critique, even for such women, often fails to be effective when they turn from teaching and writing to problems of family and personal relationships. Turner's analysis does, however, point to some features of contemporary Western society that should not be ignored. In the first place, alternatives to male objectification of women have become possible in a society in which some legal and social constraints against women's voices and activity in the public sphere have been—and are being—lifted. Furthermore, if, in fact, an obstacle women face in their effort to build a public sphere to which they have equal access is men's anger and sense of threatened privilege, might it not be a critical time for women to formulate and present "what women want"? Suppose, for example, that women were to represent themselves as human beings embarked on a quest for carnal knowing, a self-knowledge that is not the same as the male hero's but that does, like his journey, require the public sphere and collective voice. Calypso's reminder to Odysseus offers a paradigm: "The heart within me is not of iron, but yearning, like yours." I am not your enemy, seeking to destroy your accomplishments and prevent the actualization of your longings, Calypso says, but someone with my own needs, journey, and dreams. Willingness to articulate and reveal one's own developing subjectivity can sometimes produce understanding and support instead of a response directed not to an actual woman, but to a female figure of the collective mate imagination. Frequently middle-class men who are either hostile or indifferent to feminist issues suddenly begin to understand and respect these concerns when their daughters—women whose motivating longings and delights they have known over the course of their lives—find that a profession, an institution, or a career is inaccessible or difficult because they are women. Suspect as such conversions rightly are in feminist eyes, they nevertheless suggest that collective self-representation could, in the public arena, accomplish what individual self-revelation has frequently done in private, namely, convince men of the justice of women's demand for a society in which women, like men, are encouraged to take the active and chosen risks that produce embodied self-knowledge." I do not mean to imply, however, either that women should accept the model of the male culture hero as normative or that women should appeal to men's sense of fairness in order to gain access to the "smoke-filled rooms" in which decisions that determine the quantity and quality of communal life are made. Both the privatization and the individualization of the male hero must be resisted; the solitary enlightenment of the autonomous hero cannot be women's goal. If women's self-representation seems urgent, the next question to be considered is this: Can the female body be a usable symbol for women's articulation of themselves as subjects? The fruitfulness of the female body for women's self-representation seems dubious for two reasons. First, women have been so continuously and insistently identified with the body in the Christian West that to appear to accept that identification seems counterproductive, even in a post-Christian era. Second, female nakedness has not suffered from a lack of representation, but has, as we have seen, received the constant attention of male authors and artists; female nakedness has been heavily invested with social and religious meanings. Vision, the activity of seeing, does not occur independently of the associations provided by public meanings. And the female body which has played such a central historical role in the circulation of meaning in the Christian West is perhaps too assimilated to the male gaze to permit inscription with new meaning, with a female-defined sexuality and subjectivity. Female nakedness is, after all, at least as vigorously appropriated to the male gaze in twentieth-century media culture as it ever was. Female nakedness and its corollary, the disengaged male gaze—scopophilia—are systematically woven into the routine expectations of a media culture. The freight and weight of public representations of female bodies cannot be quickly overcome by women who wish to use the female body to represent and symbolize women's subjectivity.

Nor is the problem simply that the female body is assimilated to the male gaze. In an important article, "The Esthetics of Power in Modern Erotic Art," Carol Duncan has argued that "the nude in her passivity and impotence (sic] is addressed to women as much as to men," for "far from being merely an entertainment for males, the nude as a genre is one of many cultural phenomena that teaches women to see themselves through male eyes and in terms of dominating male interests."15 Women, whose visual training by the communication media has been virtually identical to that of men, have, like men, a subjectivity that is "crucially constituted by relations of looking."16 Women, like men, acquire "a sense of subject set off against objects through active looking," so that women, insofar as they develop subjectivity, do so by occupying "the position of the male gaze."17 The complex dynamic in which subjectivity belongs to the one who looks, and objectivity to the one looked at, will be difficult for women to change, not only in society, but in our own visual practices. Another condition identified by feminists as necessary for the effective representation of female nakedness as an expression of women's sexuality and subjectivity seems unlikely to be achieved in the foreseeable future. Men must relinquish the figure of the naked female as a format for the representation of male sexuality and must learn to represent themselves in more direct and honest ways. As Hélène Cixous has said:

Certainly, when a new idiom for male sexuality replaces the use of the female body as a cipher for male desire, the female body, divested of its status as "occupied territory,"19 will be more readily available to women's art and literature. . An intricate debate, which I will not reproduce here, has converged around issues related to the use of the female body in women's self-representation.20 It is significant that, as Craig Owens writes, "few [women artists] have produced new 'positive' images of a revised femininity" and that "some refuse to represent women at all, believing that no representation of the female body in our culture can be free of phallic prejudice."21 And Lisa Tichner has said that in the present "inherited framework" in which women artists work, "women's body art is . . . to a large extent reactive, basically against the glamourous reification of the Old Master/Playboy tradition, but also against the academic convention in so far as that, too, continued to see the female body as a special category of motif "22 French feminists like Hélène Cixous, Luce Irigaray, and Julia Kristeva have urged women to "write the body," to formulate subjectivity as physical experience and in so doing to repossess the female body.23 Visual artists have also experimented with a variety of presentations of the female body, but feminist critics like Lucy Lippard have been less certain of the effectiveness of female body images in a society in which these are easily accommodated to the established visual dynamic of the male gaze and the female object. Is there a "women's art" arising from a distinctive female biology, experience, or sexuality?24 The question has evoked different responses from women artists and feminist critics. Twentieth-century artists like Georgia O'Keeffe and Judy Chicago, to name only the best known, have used vaginal imagery extensively. They have, however, interpreted their use of female body imagery differently. O'Keeffe refused to think of or present herself as a "woman artist," finding that designation oppressive in an art world dominated by male artists and critics. Judy Chicago, on the other hand, insists on being understood as a woman artist; she established the first feminist art collective and wanted her work to be seen "in relation to other women's work, historically, as men's work is seen."25 Chicago has also claimed that women artists share a common preoccupation with the female body, a characteristic "female imagery," a claim denied by other women artists and critics.26 More recently, the work of Sherrie Levine and Cindy Sherman illustrates the painful difficulty postmodern women artists experience in attempting to develop artistic forms that belong to women and express their subjectivity. Levine's work, from about 1978 to 1984, refused to use the female body as an expressive medium. Instead, she appropriated the imagery of other artists. She rephotographed the photographs of Edward Weston, Eliot Porter, Walker Evans, and others, and she created collages from cut-up reproductions of paintings and watercolors by such artists as Van Gogh, DeKooning, Kirchner, and Matisse. According to the critic Douglas Crimp, Levine did this to insist that art is "always a representation, always-already-seen."27 Her work can thus be seen as "a radical critique of the most hallowed of art historical principles: the originality and expressiveness of the artist. "28 Levine's extreme self-effacement as artist, however, while it may dramatize the absence of women from public self-representation, has not suggested directions for the future of women's art. Cindy Sherman works quite differently with the question of what a woman artist can represent. Although her photographs are usually of herself and/or objects intimately associated with her body (sunglasses, clothing, blood, vomit), Sherman "claims not to be present" in photographs of herself. Rather, her "presence" is that of "a series of stock personalities"29 belonging to the object "woman." Sherman has been criticized for the way her self-images accept and invite the conventional male gaze. In several photographs she poses in bra and panties on a bed; others show her cringing from the gaze of the male spectator. Though visible, her body reveals only the absence of Cindy Sherman as subject. Like Levine, Sherman dramatizes the exclusion of women from public self-representation but fails to suggest visual strategies that would permit women to present themselves as subjects in their art. Essentialist versus social theories of sex and gender reappear in these debates about women's self-representation in art and literature. For example, Elaine Showalter has argued against essentialist understandings like Cixous's in which women are urged to "write the body." While acknowledging the potential importance of female body imagery in women's literature, Showalter concludes that "there can be no expression of the body which is unmediated by linguistic, social, and literary structures." She proposes a theory of women's culture that "incorporates ideas about women's bodies, language, and psyche, but interprets them in relation to the social contexts in which they occur."30 If there is any agreement among adherents of social and essentialist theories, however, it is in finding that too great a loss and deprivation for women is entailed in deciding that the female body has been irretrievably appropriated to male agenda. Lisa Tichner has outlined two courses of action presently open to women artists: "one is to ignore the whole area as too muddled or dangerous for the production of clear statements; the other is to take the heritage and work with it—attack it, reverse it, expose it, and use it for their own purposes."31 Tichner recommends that women artists reclaim the female body from masculine fantasy and "authenticate and reintegrate 'lost' [that is, unrepresented] aspects of female body experience." This reintegration will require, Tichner says, a "de-colonizing" and "de-eroticizing" of the female body.32 To begin that enterprise, women must first identify the techniques men use to colonize and eroticize the female body and then devise alternatives. In the last chapter of her study of representations of the female body in Victorian literature, The Flesh Made Word, Helena Michie concludes that "full representation of the body is necessarily impossible" in a language that depends for meaning on absence and difference. Nonetheless, she identifies—helpfully for our purposes—a device characteristically employed in male representations of female bodies that directly undermines representation of women as subjects. Fetishization of parts of the body—breasts, legs, vulva, uterus—she says, transgresses the body's integrity as subject. Underlying her analysis is the principle that "the recreation of the female body with its many zones of pleasure and playfulness depends on a respect for its integrity."33 This suggests that the female body must be represented in ways that visually focus the whole body equally. In other words, it is a "naked," not a "nude," body that is able to bear the weight of women's self-representation.34 The nude body, is, in Kenneth Clark's magisterial definition, passively positioned for the male gaze with its greater interest in some parts of the female body than others. Women artists should also avoid encouraging a voyeuristic gaze in self-representations that use the female body as a symbol of subjectivity. For, as Iris Young notes:

Like men, women will need the commitment and self-discipline requisite to learning a new response—in the face of an inadequate response that has become habitual—if we are to look at a representation of a naked woman not with an appraising patriarchal eye, but with an eye that identifies with the person represented. This identification is a necessary preliminary step toward noticing and understanding the visual clues that make that person's interior life accessible. New visual skills are difficult, even painful, to learn. It is not easy to discern the presence of a subject in visual images in which formerly an object has "caught the eye." Because of this difficulty, not many people will undertake to retrain themselves visually. Thus, a new discipline of seeing cannot be proclaimed as a panacea, a correction for the exclusion of women as subject in Western art and literature. But when feminist artists and authors "paint the body" and "write the body" as the perfect expression of female subjectivity, this art begins to create a new kind of "spectator" a viewer whose aesthetic experience is more like making an acquaintance than like surveying an object.36

In women's public self-representations, the female body must look different from the way it does as the expression of male desire. As in Valadon's Self-Portrait, different visual strategies can create a different relation between image and viewer. Perhaps for some time to come, women artists and authors will need to experiment with images, material, styles, and media for self-representation. But women must also learn to see differently if their collective public self-representations are not to reflect the introjected male gaze. Women, visually trained in patriarchal societies to see ourselves and other women as objects, can reject the visual values and artistic devices by which women are relegated to objectivity. We can cease to evaluate ourselves and other women on the basis of our ability to attract and hold the gaze that grants us existence and visibility. We can alter our visual practices by learning to see and read the female body as the intimate reflection and articulation of women's subjective experience. As the German feminist Frigga Haug said, "Our aim is to reach a point at which we no longer see ourselves through the eyes of others."39 Much of the content of this book has revolved around religious practices and representations of female nakedness in the Christian West, yet the conclusions I have drawn thus far have focused exclusively on the contemporary concerns of secular feminists. What relevance do the gendered practices and representations of women of historical Christian societies have for a contemporary culture frequently characterized as post-Christian The central project of Christianity, I suggest, has been subverted by the representational practices of the Christian West. That project, formulated doctrinally as the incarnation of God in human flesh, is carnal knowing, embodied knowledge. It is experiential understanding that is aware and respectful of the particular and concrete conditions in which all learning occurs, whether that learning is named as socialization, religious orientation, or subjectification. In Christianity, however, the flesh has largely been scorned, the body marginalized, in the project of a "spiritual" journey. Christian doctrinal affirmation of human bodies is unambiguous; doctrines of creation, the incarnation of Christ, and the resurrection of the body clearly posit a faith in which bodies are integral. Yet faith, knowledge of self and world, and spiritual progress came to be seen as abstract; at best, the energy and vitality of the body could be usurped for the creation and cultivation of a religious self. Counterinstances can certainly be found to disparagement of the body; one of them, naked baptism, I discussed extensively in chapter 1. My goal in that chapter was not only to describe Christian baptism as gendered, but also to explore the thoughtful, systematic inclusion of bodies in the essential initiation of all Christians. Why did "the flesh" become marginalized in Christianity? It was not, as has often been charged, Christianity's self-identification with philosophy that most decisively created the view that knowledge at its best is free of the flesh, spiritual rather than carnal, unaffected by the intimate and concrete circumstances of the human being to which it belongs as knowledge. It was, rather, the sexism of Christian societies, revealed most clearly in representational practices that created this view and fatally undermined the Christian project of integrating the flesh. By identifying men with rationality and "woman" with body, and by rhetorical and pictorial practices that denigrated women in relation to men, Christian societies effectively ghettoized the flesh, undermining even the strongest doctrinal ratifications of "the body." In Christianity the body scorned, the naked body, is a female body. Ironically, the contemporary feminist concern for recovering the female body lies at the heart of the ancient Christian project. To represent the female body, not as erotic—as "erotic" has been culturally constructed—not as the object of fascination and scorn, but as revelation and subjectivity is to correct and complete the Christian affirmation of body. It is to present the flesh, not made word, but given voice to sing its own song. NOTES 1. Hélène Cixous, "The Laugh of the Medusa," Signs (Summer 1976): 40. 2. Lisa Tichner, "The Body Politic: Female Sexuality and Women Artists Since 1970," Art History 1 (1978): 247. 3. Ibid., 220. 4. Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 279. 5. Sandra Lee Bartky, "Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power," Feminism and Foucault, 72. 6. Jana Sawicki, "Identity Politics and Sexual Freedom: Feminism and Foucault, in Feminism and Foucault, 187. see also my article, "Generosity and Suspicion: Theological Education in a Pluralistic Setting," Theological Education 23, Supplement (1987), for an account of the value of difference in an academic setting. 7. Bryan S. Turner, The Body and Society (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1984), 3. 8. Ibid., 152-53. 9. Ibid., 155. 10. Ibid, 11. Ibid., 156. 12. Ibid., 145. 13. In The Bonds of Love: Psychoanalysis, Feminism, and the Problem of Domination (New York: Pantheon, 1988), Jessica Benjamin argues that male domination and female submission cannot be fully understood by examining only the social interaction of men and women, but must be seen as an "interaction of culture and psychological processes" (81). Both female masochism and male sadism, she claims, originate with "the mother's lack of subjectivity, as perceived by both male and female children" (81). The mother's lack of subjectivity occurs because, in the marital relationship, "one person (the woman) is not allowed to play the subject; one person (the man) arrogates subjectivity only to himself" (82). Because of the mother's "renunciation of her own will," she cannot respond to the child's self-assertion with both recognition and limit-setting. Even more problematically, she cannot require from him recognition of herself as an individual with her own needs. In Benjamin's striking phrase, mother and child commit "the original sin of denying recognition to the other" (83 -84). The result is the reproduction of gender polarity and complementarity, rather than mutuality. Mutual recognition, the decisive moment in which sameness and difference are acknowledged, requires the presence of two subjects. Whether we begin with social practices or intersubjective processes, then, the result is similar: women's lack of a developed and confident subjectivity both results from, and perpetuates, gender asymmetry. Nevertheless, Benjamin's optimism over the possibility that "individuals can integrate the gender division, the two sides of which have previously been considered mutually exclusive and the property of only one sex" (130) seems unwarranted if it is exclusively based on alterations in the dynamics of intersubjectivity. Until the development of women's subjectivity is valued in the public sphere, and reflected and cultivated in social practices and representations, I suspect that real intersubjective changes between men and women will be impossible. 14. See Jane Caputi's analysis of the interconnection of misogynist society, media culture, and serial murders: The Age of Sex Crime (Bowling Green: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1987). 15. Carol Duncan, "The Esthetics of Power in Modern Erotic Art," Heresies 1 (1977): 47. 16. Iris Marion Young, "Women Recovering Our Clothes, Perhaps," in Postmodernism and Continental Philosophy, ed. Hugh J. Silverman and Donn Welton (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1988), 146. 17. Ibid., 147. 18. Cixous, "The Laugh of the Medusa," 247. 19. Tichner, "The Body Politic," 239. 20. Thalia Gouma-Peterson and Patricia Matthews, "The Feminist Critique of Art History," The Art Bulletin 69:3 (September 1987): 326-57, provides extensive bibliography on this issue. 21. Craig Owens, "The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism," in The Anti-Aesthetic, Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Post Townsend, WA: Bay Press, 1983), 71. 22. Tichner, "The Body Politic," 239. 23. Cixous's advocacy of "writing the body" is founded on an essentialism that identifies women with body: "More so than men who are coaxed toward social success, toward sublimation, women are body. More body, hence more writing" ("The Laugh of the Medusa," 267). 24. For example, Ruth Iskin formulates the possibility of a "women's art" in the following way: "What does it feel like to be a woman? To be formed around a central core and have a secret place which can be entered and which is also a passageway from which life emerges? What kind of imagery does this state of feeling engender? There is now evidence that many women artists have defined a central orifice whose formal organization is often a metaphor for a woman's body. The center of the painting is the tunnel, the experience of female sexuality." See "Sexual and Self-Imagery in Art—Male and Female," Womanspace Journal 3 (June 1973): 11. 25. "Judy Chicago, Talking to Lucy Lippard," in Lucy R. Lippard, ed., From the Center: Feminist Essays on Women's Art (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1976), 219. 26. Ibid., 227: "I never meant all women made art like me. I meant that some of us had made art dealing with our sexual experiences as women. I looked at O'Keeffe and Bontecou and Hepworth and I don't care what anybody says, I identified with that work. I knew from my own work what those women were doing. A lot of us used a central format and forms we identified with as if they were our own bodies.... I really think that differentiates women's art from men's." 27. Douglas Crimp, "The Photographic Activity of Postmodernism," October 15 (Winter 1980): 98. 28. Deborah Haynes, "A Look at What Belongs to What: The Art of Sherrie Levine and Cindy Sherman," unpublished manuscript, October 1988. 29. Peter Schjeldahl and Lisa Phillips, Cindy Sherman, Essays (New York: Whitney Museum of Modern Art, 1987), 16. 30. Elaine Showalter, "Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness," in The New Feminist Criticism, ed. Elaine Showalter (New York: Pantheon, 1985): 252, 259. 31. Tichner, "Body Politic, " 239. 32. Tichner, I assume, uses Carol Duncan's definition of "erotic" as "erotic for men" in advocating the "de-eroticizing" of the female body. 33. Helena Michie, The Flesh Made Word, Female Figures and Women's Bodies (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 141. 34. See, for example, the late-nineteenth-century portraits of Suzanne Valadon, of which Ruth Iskin writes: "Suzanne Valadon's paintings ... represent undressed women models, whose figures are robust and heavy; not beautiful in the traditional sense, their age, life, and sufferings are visible. They are powerful images of women as real living members of society." Iskin also proposes that the self-portraits of the twentieth-century artist Marriette Lydis "transcend a male view of a female nude." Iskin, "Sexual and Self-imagery," 9-10. 35. Young, "Women Recovering Our Clothes," 146. 36. Hans-Georg Gadamer's description of what he calls "the experience of art" (as opposed to "aesthetic experience") describes a visual hermeneutic in which viewer and art "object" enter something like a conversation in which both are changed because of the other's presence; the work of art is changed in interpretation, and the viewer is changed because of the new experience represented by the work of art. Gadamer, Truth and Method (New York: Crossroad, 1984), section 1. 37. Betterton, "How Do Women Look? The Female Nude in the Work of Suzanne Valadon" Feminist Review 19 (March 1985), 258. 38. Ibid., 266. 39. Frigge Haug, ed., Female Sexualization, trans. Erika Carter (London: Verso, 1987). 39. |

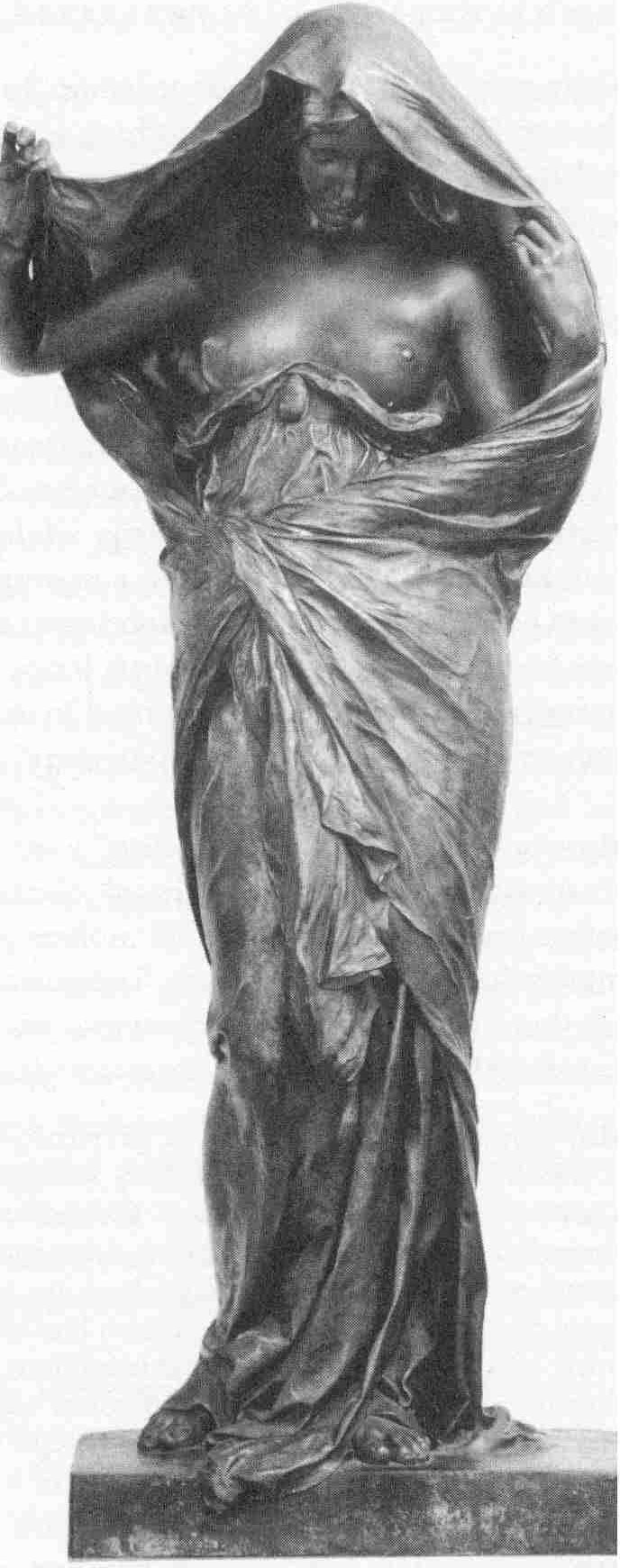

(See figure of

Louis-Ernest Barrias, "Nature Revealing Herself to Science, late nineteenth century).

In fact, representations of women may be the cultural artifact on which men find most

unanimity. Women's self-representations, on the other hand, can seek and delight in the

diversity among women, can endeavor to articulate difference rather than sameness.

Whatever is common to women or similar about women must emerge from a multitude of

self-representations of difference rather than from coercion, however subtle, to

demonstrate "unity." Differences within the discourses that create women's

collective voice are "a resource rather than a threat."6 The

Enlightenment project, the overcoming of dissent by rationality grounded in a

transcendental subjectivity, cannot be the goal of female collective voice.

(See figure of

Louis-Ernest Barrias, "Nature Revealing Herself to Science, late nineteenth century).

In fact, representations of women may be the cultural artifact on which men find most

unanimity. Women's self-representations, on the other hand, can seek and delight in the

diversity among women, can endeavor to articulate difference rather than sameness.

Whatever is common to women or similar about women must emerge from a multitude of

self-representations of difference rather than from coercion, however subtle, to

demonstrate "unity." Differences within the discourses that create women's

collective voice are "a resource rather than a threat."6 The

Enlightenment project, the overcoming of dissent by rationality grounded in a

transcendental subjectivity, cannot be the goal of female collective voice. Edwina Sandy's Christa

(See figure.) illustrates the danger of appropriating the naked female form to present

women's experience. Here a crucified woman droops on an implied cross, thus occupying what

is perhaps the position of greatest honor in centuries of Christian depictions of Christ's

redemption of the world. The image startles; it makes vivid the perennial suffering of

women. As a private devotional image it may have great healing potential for women who

have themselves been battered or raped. Yet as a public image, placed for some time in the

Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City, there are fundamental problems with

the image. The Christa, by its visual association with the crucified Christ,

glorifies the suffering of women in a society in which violence against women has reached

epidemic proportions.14 Equally disturbing is its association with pornography,

which similarly fetishizes suffering women. The naked and tortured female body has been

appropriated by a media culture and cannot therefore be arbitrarily assigned religious

meaning. The Christa cannot communicate religious meaning in twentieth-century

Western culture any more than sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings of Susanna and

the Elders could effectively communicate Susanna's innocence in societies in which, for

centuries, female flesh had symbolized sin, sex, and the fall of the human race.

Edwina Sandy's Christa

(See figure.) illustrates the danger of appropriating the naked female form to present

women's experience. Here a crucified woman droops on an implied cross, thus occupying what

is perhaps the position of greatest honor in centuries of Christian depictions of Christ's

redemption of the world. The image startles; it makes vivid the perennial suffering of

women. As a private devotional image it may have great healing potential for women who

have themselves been battered or raped. Yet as a public image, placed for some time in the

Cathedral of Saint John the Divine in New York City, there are fundamental problems with

the image. The Christa, by its visual association with the crucified Christ,

glorifies the suffering of women in a society in which violence against women has reached

epidemic proportions.14 Equally disturbing is its association with pornography,

which similarly fetishizes suffering women. The naked and tortured female body has been

appropriated by a media culture and cannot therefore be arbitrarily assigned religious

meaning. The Christa cannot communicate religious meaning in twentieth-century

Western culture any more than sixteenth- and seventeenth-century paintings of Susanna and

the Elders could effectively communicate Susanna's innocence in societies in which, for

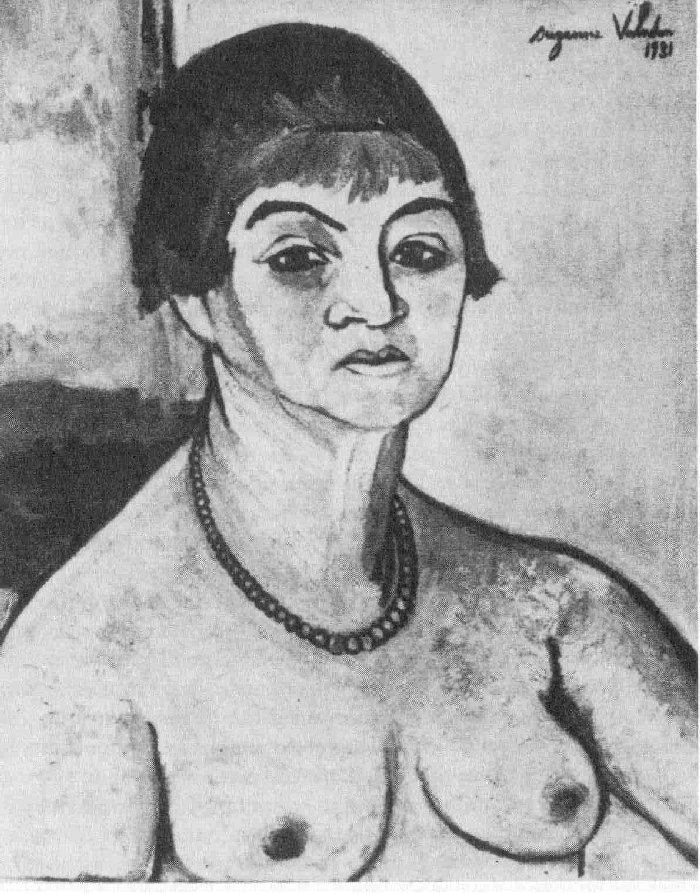

centuries, female flesh had symbolized sin, sex, and the fall of the human race. One of Suzanne

Valadon's self-portraits provides an example of female nakedness presented as symbol and

site of a woman's subjectivity (See figure.). Her 1932 Self-Portrait, painted when

she was sixty-seven, shows her naked upper body. Upright-seated or standing—the

figure meets the viewer's eye directly. Filling the picture frame, she seems uncomfortably

close to the viewer, thereby resisting the distanced eye of the voyeur. Her gaze seems to

replace or overwhelm that of the viewer. The bottom edge of the painting abruptly elides

the woman's right breast just under the nipple, refusing the fetishist's pleasure in

seeing the shape of the breast. "Dressed" in a necklace, with combed hair and

made-up face, the figure presents herself as she wishes to be seen. She appears

self-possessed and self-conscious, her body herself, who she is, indifferent to the

viewer's projections, and deliberately not endeavoring to attract the gaze or desire of a

male viewer. It is not accidental that Valadon, a professional artist's model for about

ten years,37 chose to present herself as subject in her own painting. Filling

the picture space reserved in patriarchal culture for the young, attractive female nude

with an older woman who stares, rather than attracts stares, Valadon effectively

challenges the patriarchal identification of "woman" with female flesh. She

repossesses the female body for a woman's subjectivity, "showing [a woman’s]

nakedness as an effect of particular circumstances . . . differentiated by age and

work."38

One of Suzanne

Valadon's self-portraits provides an example of female nakedness presented as symbol and

site of a woman's subjectivity (See figure.). Her 1932 Self-Portrait, painted when

she was sixty-seven, shows her naked upper body. Upright-seated or standing—the

figure meets the viewer's eye directly. Filling the picture frame, she seems uncomfortably

close to the viewer, thereby resisting the distanced eye of the voyeur. Her gaze seems to

replace or overwhelm that of the viewer. The bottom edge of the painting abruptly elides

the woman's right breast just under the nipple, refusing the fetishist's pleasure in

seeing the shape of the breast. "Dressed" in a necklace, with combed hair and

made-up face, the figure presents herself as she wishes to be seen. She appears

self-possessed and self-conscious, her body herself, who she is, indifferent to the

viewer's projections, and deliberately not endeavoring to attract the gaze or desire of a

male viewer. It is not accidental that Valadon, a professional artist's model for about

ten years,37 chose to present herself as subject in her own painting. Filling

the picture space reserved in patriarchal culture for the young, attractive female nude

with an older woman who stares, rather than attracts stares, Valadon effectively

challenges the patriarchal identification of "woman" with female flesh. She

repossesses the female body for a woman's subjectivity, "showing [a woman’s]

nakedness as an effect of particular circumstances . . . differentiated by age and

work."38