|

Margaret R. Miles, "Introduction," Carnal Knowing: Female Nakedness and Religious Meaning in the Christian West (Vintage 1989) 1-18.

INTRODUCTION The discourse of man is in the metaphor of woman.1 The enigma that is woman will therefore constitute the target, the object, the stake, of a masculine discourse, of a debate among men, which would not consult her, would not concern her.2 Any theory of the subject has always been appropriated by the "masculine."3 Culture, as we know it, is patriarchy's self-image. The history of representation is the history of the male gender representing itself to itself.4 Today there is a great deal of thought against representation. In a more or less articulated or rigorous way, this judgment is easily arrived at: representation is bad. . . . And yet, whatever the strength and the obscurity of this dominant current, the authority of representation constrains us, imposing itself on our thought through a whole dense, enigmatic, and heavily stratified history. It programs us and precedes us and warns us.5 In about 2800 B.C. a Babylonian scribe put in writing the saga of the legendary king Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh, so the tale goes, was two-thirds god and one-third man. His appetites were voracious and his energy limitless, and he did not learn easily. At the opening of the epic, Gilgamesh's people are distressed at his lordly indifference to their feelings. He insisted, for example, on being the first to have sexual intercourse with every bride. Although we have no report from the ancient scribe as to the brides' feeling about this "honor," we are told that the practice offended husbands and fathers. They complained, but, of course, without effect. After groaning under this oppression for many years, the people found a champion, Enkidu, perhaps the strongest man alive, who might give Gilgamesh the unprecedented and edifying experience of being defeated in a fight. Enkidu had a strange history. He had been a wild man, running with the gazelles, feeding amiably with the lions, and sleeping in the forest, until he was captured and brought to the temple. There, an unnamed prostitute tamed him by teaching him the art of lovemaking and the ways of civilized people. His strength, once equal to the lions', and his speed, once equal to the gazelles', diminished rapidly, but he still possessed more strength and speed than any other man, except, possibly, Gilgamesh. One day when Gilgamesh strode through the streets on his way to a bride, the people set Enkidu on him. They fought, and for the first time in his life Gilgamesh was prevented from accomplishing the satisfaction of his sexual desire. Rather than resenting this frustration, however, he immediately respected and loved the man who had proved his equal in strength and resolve. Enkidu and Gilgamesh became friends and shared many adventures, dangers, and triumphs, until, in the midst of one of their heroic battles, Enkidu was killed. Gilgamesh was inconsolable at Enkidu's death, for he had lost the one person he loved. Moreover, Enkidu's death made him realize that a similar fate awaited him. Unwilling to accept his own mortality, Gilgamesh, in characteristic fashion, resolved to do something about it. He had heard that there was one man, Utnapishtim, who had survived the deluge that destroyed the human race and who, alone of all mankind, had been granted immortality by the gods. Gilgamesh set out to find him, intending to force him to give up the secret of immortality. To Gilgamesh's credit—he had learned something about fellow feeling from his experience of human limitation and love—he wanted to obtain everlasting life not only for himself, but also for his people. As he journeyed in search of Utnapishtim, Gilgamesh came to the garden of the gods, a garden lush with bushes on which grew precious gems—carnelian, lapis lazuli, agate, and pearls. There, at the edge of the shining sea, he met a young woman who brewed in golden vats the intoxicating drink of the gods. Siduri saw Gilgamesh approaching, "wearing skins, the flesh of the gods in his body, but despair in his heart." She could hardly believe that this skinny, despairing, weather-beaten man was the legendary Gilgamesh. But he explained his anguish over Enkidu's death and his fear of his own death and then asked her to help him find Utnapishtim. Before reluctantly directing him to the next stage of his journey, however, Siduri gave him some advice:

Needless to say, Gilgamesh did not heed this advice, and hurried away to pursue immortality. The epic closes with Gilgamesh's death and the ritual lament of his people for a king who, although he was two-thirds god and one-third man, in his death was only human. Using the metaphor of heroic struggles in the external world, The Epic of Gilgamesh narrates the development of male subjectivity. Three women or groups of women appear in the epic as foils for the hero's developing awareness of what is entailed in being human. First are the brides, undifferentiated and nameless women, who are raped by Gilgamesh. They present no challenge to Gilgamesh's unlimited aggression and self-assertion, and they do not stimulate in him any awareness of the real existence of another human being. Second is the temple prostitute, who, in teaching Enkidu the art of lovemaking, tames him and reduces his strength to a level acceptable and useful to society. Third is Siduri, the only human woman named in the epic,7 who momentarily halts Gilgamesh in his frenzied quest for everlasting life and advises him to notice and enjoy the beauties and loves of this earth, the "lot of man," instead of disregarding these accessible delights and pursuing an unobtainable goal. The temple prostitute raises Enkidu above the beasts, and Gilgamesh reduces him from a god, thereby defining the lower and upper limits of the human. These women appear in the first extant text that depicts heroic struggle against the restraints of humanness. The text focuses on the development of the hero, Gilgamesh; the women's subjectivity does not develop. The women instead "stand for" twin male dilemmas: they are the endlessly replaceable objects of the hero's insatiable lust, and they represent the arbitrary limitations on an individual's potential imposed by society and mortality. Moreover, no reconstruction of these women's perspectives through their physical experiences is given; the interdependence of body and consciousness that has played such a prominent role in the humanization of the hero is missing from the text's representation of the women. Where is the epic of Siduri? Why was her wisdom presented only as a foil for Gilgamesh's aspirations? What physical experiences, what struggles, shaped her self-understanding and the philosophy of life she articulated. so poignantly? Women are not incidental to telling the hero's story; indeed, they play an essential and highly visible role in his development. Mothers, sisters, lovers, wives, daughters, and anonymous women are crucial to the definition and refinement of male subjectivity. Yet female subjectivity did not, until the nineteenth century, begin to receive the exploration accorded that of men. Female subjectivity has occasionally appeared furtively in early Western literature, embedded in texts whose project was to describe a male journey. The story of Odysseus and Calypso in book 5 of The Odyssey, for example, includes a female character who reminds the hero of her subjectivity. Because Odysseus knows that Calypso loves him and that his preparations to leave hurt her, he suspects her of plotting to prevent his departure. Calypso assures him that, though his departure grieves her, she will do nothing to stop him; she understands his longing to sail for home, she says, but she also urges him to pause long enough to recognize her feelings. He has construed her as an enemy in order to rationalize hurting her, a dishonest and unnecessary ploy, a stratagem that specifically denies her subjectivity, for, she says, "The heart within me is not of iron, but yearning, like yours." Yet where can we read the epic of Calypso? Odysseus's representation of Calypso as the villain he needed her to be in order to leave her is reiterated in her literary role as nothing more than a moment in his journey. Such an act of representing can be seen as a "laying hold and grasping,"

"an objectifying that goes forward and masters."8 It is one component

of the representations—mostly men's representations of women—that will occupy us

throughout the book and one of several definitions that underlie the discussion. As a

noun, a representation is a description or visual depiction of an object; as a verb, to

represent is to characterize an object according to an (always perspectival) analysis of

the essential or distinguishing features of the object. The activity of representing entails two interdependent and simultaneous motions: the characterization of an object and the articulation of a subject's judgment. Further, people do not grasp something we like to call "reality" directly, but through representations of culturally construed reality. The power of representation is thus closely related to and dependent on politics and social institutions. The crucial questions about representation are: Who has the power of representation in a particular culture? Who can be represented and how? And by what "system of power" are certain representations authorized while others are blocked, prohibited, invalidated, or ignored?9 Theories of representation, though they have perhaps received more scholarly attention since Kant, are not exclusively a modern concern. The ancient doctrine of phantasms, described by Plato and developed by Aristotle, was rediscovered and reinterpreted in the Renaissance. The persistence of the theory demonstrates historical people's continuing interest in representation and its effects. Representation is necessary, according to Aristotle, because the soul has no sense organs with which to grasp the phenomena of the sensible world, and the body, without the soul, has no ability to codify and retain messages brought by the sense organs. "Body and soul speak two languages, which are not only different, even inconsistent, but also inaudible to each other."10 Therefore, an "inner sense"11 must coordinate and translate messages received from the body; it must, in essence, create a picture or sequence of pictures within the soul, using the "stuff" of the soul, pneuma, to create these phantasms.12 The soul must create these impressions from the body before it can understand anything about the sensible world. The physical or quasi-physical nature of this process was emphasized by the Stoics, for whom pneuma—spirit—was a material, though highly attenuated, substance. Joan Culianu traces the "effective history"13 of the theory of phantasms as it was used by later authors to explain sexual attraction; Andreas Capellanus, in his treatise On Love, written in the twelfth century, said:

It was this reconstruction of the dynamic of desire that prompted the thirteenth-century poet Giacomo da Lentino to ask: "How can it be that so large a woman has been able to penetrate my eyes, which are so small, and then enter my heart and my brain?"15 Representation theory entered the modern world with Kant's Critique of Judgment, which

presented an aesthetic theory that jettisoned the quasi-physical nature of the theory of

phantasms but retained its emphasis on the activity of inner representation. The problem

Kant sought to explain is how a subject makes aesthetic judgments. Restating the ancient

principle that man is the measure of all things, Kant wrote: "In order to distinguish

whether anything is beautiful or not, we refer the representation, not by the

understanding to the object, but by the imagination . . . to the

subject and its feeling of pleasure or pain."16 Kant's aesthetic theory

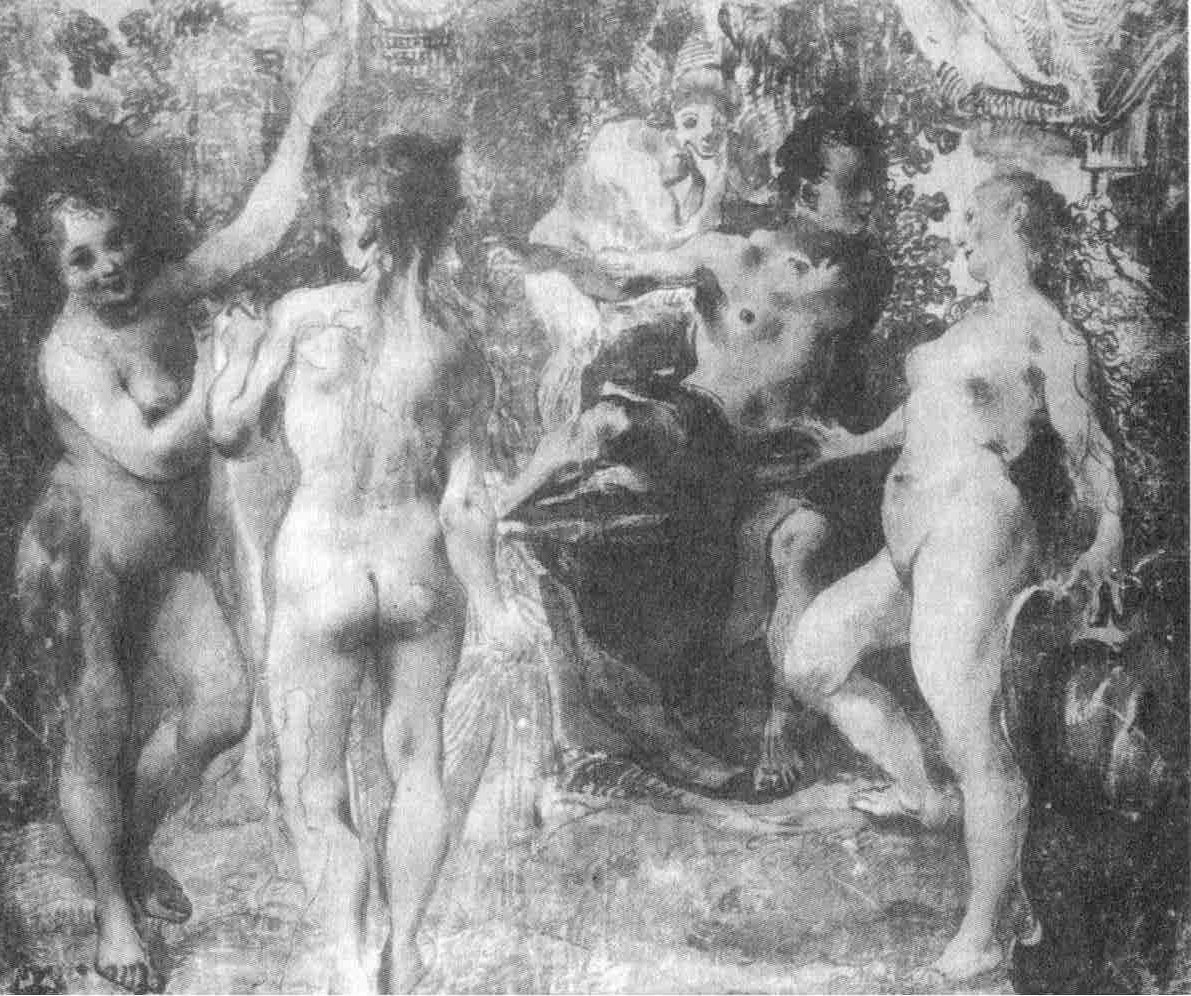

might be understood as a sort of "Judgment of Paris," in which three goddesses

subject their beauty to the evaluation of a man, in whose eye—"the eye of the

beholder"—beauty is created (figure - Annibale Carracci, Judgment of Paris c.

1584). The subject's judgment is, in Kant's description, also universal. The subject's alleged "disinterest" makes it so. There is no "satisfaction connected to desire" attached to this judgment; it is, purely and simply, an objective judgment of taste. Emptied of any self-interest, the subject's judgment can be legitimately projected onto the object as a feature of the object: beauty. Kant also claimed that everyone who has "taste" would necessarily make a similar judgment. In fact, the test of whether a person has taste is whether s/he agrees with the judgment. The subject's judgment is universally binding. The question that arises from Kant's analysis of aesthetic judgment is this: Who possesses the privileged judgment of "the subject"? Susanne Kappeler has noted that in Kant's theory "the position of the subject, in principle, is open to all people, but in practice the principle of universal validity has been tested among a limited number of subjects."19 Francis Barker adds, "The healthy male body [is] the only official vessel for lawful subjectivity. "20 In addition to gender assumptions, Kant's expectation that "the subject" will occupy a certain class, educational, and institutional niche is also apparent.21 Those biases have been carried forward into the twentieth century. When in 1938 Martin Heidegger claimed "that the world exists only through a subject who believes that he is producing the world in producing its representation,"22 he transformed the world into a representation, with man as its subject.23 While more recently the universal judgment of the socially and economically privileged subject has been questioned and rejected,24 "it is [still] the man who speaks, who represents mankind. The woman is only represented; she is (as always) already spoken for."25 The hero's construction as subject in works like The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Odyssey, entails a journey to self-knowledge achieved through physical struggle, labor, and pain. The hero's self-knowledge is carnal knowledge, awareness recorded in the body. One who has not experienced limitation and suffering cannot recognize the suffering of others and cannot locate himself in a human community shaped by awareness of limitation and mortality. The consanguinity of human beings depends on mutual recognition of the common bond of a sentient body, whose most vivid experiences create consciousness. Millennia after The Epic of Gilgamesh, in the societies of the Christian West, an understanding of oneself as body was produced by gendered religious practices and recorded in texts and visual images that represented men's and women's bodies as symbolic of different religious meanings. Carnal knowing—embodied self-understanding—needs to be distinguished, however, from historical and contemporary meanings of "carnal knowledge." "Carnal knowledge," a term from medieval canon law, means sexual intercourse. Yet a broader meaning is implicit in the several meanings for the adjective "carnal" listed by the Oxford Dictionary of the English Language: (1) of, or pertaining to, flesh or body; (2) related in blood, as in the phrase "according to the flesh"; (3) pertaining to the body as the seat of the passions or appetites, fleshly, sensual; (4) not spiritual, but material.26 The first two meanings are neutral in value; the second two contrast whatever relates to body with what is spiritual, implying the greater value of the spiritual. Curiously, although the term itself seems to suggest that embodied knowledge of oneself and another human being can be attained in the intimacy of lovemaking, in usage "carnal knowledge" implied that lovemaking is defined by, if not limited to, its physical aspect. The qualifier "carnal" effectively canceled recognition that either intellectual or spiritual understanding can occur.27 Is "carnal knowing," then a contradiction in terms? In the Western philosophical tradition reason has often been "assumed to be disembodied and abstract," independent of physical experience.28 In striking contrast to philosophers' esteem for "reason alone," Tertullian, a third-century North African Christian, wrote:

In spite of Tertullian's recognition that the soul is always dependent on the body, however, it is difficult to support my use of "carnal knowing" as embodied self-knowledge from the dominant philosophical or religious traditions of the West. Rather, the historical use of the term signals, ironically, the dualistic assumptions of Western philosophy and Christian theology. In my usage, "carnal knowing" suggests minimally (as in Tertullian's description) that the brain in which thinking occurs is a material substance. Beyond this, "carnal knowing" refers to an activity in which the intimate interdependence and irreducible cooperation of thinking, feeling, sensing, and understanding is revealed. Carnal knowing is both embodied and social; It includes the most private and intimate experiences as well as the most public and social experiences. Carnal knowing is not a kind of "pure" subjectivity, untouched by social location and by all the particularities of experience that create one's perspective. Rather, subjectivity is itself a social construct, a cultural artifact, as Rom Harré notes: "Not only are the acts we as individuals perform and the interpretations we create of the social and physical world prefigured in collective actions and social representations, but also the very structure of our minds . . . is drawn from those social representations."30 Men's and women's bodies are also molded by social expectations of sex/gender difference. Ruth Hubbard has written:

Body and subjectivity have in common, it seems, a thoroughgoing vulnerability to the transformative effects of social conditioning through gendered representations. How do representations act in society? Representations both interpret and replace the objects they represent. Overlapping cumulative representations of "woman" select certain characteristics to "stand for" women, enabling men to "handle" the women to whom they must relate. The social function of representations, then, is to stabilize assumptions and expectations relating to the objects or persons represented. Image-making, E. H. Gombrich has said, "is the creation of substitutes"; an image represses by producing its symbolic representation.32 For example, literary critics like Helena Michie and Francis Barker have described a process by which the female body, transmogrified into literature, ceases to be "the immediate, the unmediated site of desire and penalty," the site of subjectivity, and becomes instead the object of writing:

Consistent, cumulative, and continuous representations of an object cause that object to "disappear" in its complex and perhaps contradictory "reality," subsumed in the "tidy, well-ordered totality" of the standardized representation.34 An established public representation, even though it may generate disagreement, resistance, and the formulation of alternatives, carries within it a behavior code. We assume that people of various races, social and economic classes, professions, and genders are as they are represented, and we treat them accordingly. Representations provide a shortcut, enabling immediate response without the laborious process of reflection that would be necessary if each person or situation were to receive an individual response. Moreover, representations often determine intimate as well as less personal relationships. Because the level of threat and the potential for pain in intimate relationships is very high, representations of the other are used to reduce her to manageability. The alternative to reliance on representations is the cultivation of a "perspectivity that confers self all around,"35 that is, that assumes that each person possesses a unique combination of integrity, intelligence, generosity, self-interest, belief, and experience. Finally, representations do not merely reflect social practices and attitudes so that analysis of representation simply reveals the prejudices or stereotypes of a society. They also re-present, reinforce, perpetuate, produce, and reproduce them.36 There is no simple causal relationship between society and representation in either direction: social practices do not determine particular representations, nor do representations specify particular social arrangements; rather, each acts on the other—to nuance or reinforce, to correct or reiterate—at myriad tiny points. The complex nature of historical evidence makes problematic any claim more specific than that of an inevitable connection between representations and social arrangements: "Causal and principled reasoning brings the [danger of] oversimplification. The linking of cause and effect works best with few variables, demonstrable relationships, and a domain of study that tends itself to compartmentalization."37 A reciprocal relationship between representations and social arrangements can, nevertheless, be assumed, and historians can proceed, without further assumptions, to explore in detail the nature of this connection in a particular society. Certainly the large picture of women's place in the societies of the Christian West can be recognized without difficulty: women have lived in male-defined and dominated societies. This fact influenced the social and sexual arrangements that shaped women's everyday lives, their self-understanding and self-images, and their development of some talents and skills at the expense of others. Even though the precise nature of the interdependence of representation and society cannot be theoretically specified, however, the politics of representation are relatively easy to identify in historical societies: who does the public representing of women, who pays for it, where it is placed, and who looks at it? One can also analyze the content of representations of women. The sex/gender systems characteristic of the societies of the Christian West, then, can be approached in two ways: first, one can analyze the content of representations of female nakedness; second, one can study the activity of representation itself. The second approach requires the political questions I have outlined, even if the historical evidence at our disposal does not always make it possible to answer them.38 The study of gender can, in addition, help us map some intimate and complex relationships among laws, medicine, social arrangements, art, government, and religion. Exploration of the interdependence of religion, gender, and culture requires an interdisciplinary approach to historical evidence. Historians find that they must learn to read pictures as well as texts; art historians recognize that they need knowledge of religious and cultural history in order to interpret a painting; feminist theorists realize that to ignore religion is to risk misrepresentation of historical women; and historians of religion discover that they cannot neglect analysis of the gender constructions at the heart of the religious literature of other cultures. For scholars trained in the discrete fields of literature, art, history, and theology, learning to use effectively the tools of other disciplines is both exciting and very hard work. It is, however, remarkably engaging work because it promises to bring us closer to a past "boiling with life," in Plotinus's phrase, than reconstructions of the past that are limited to the tools of a single discipline.39 The art and literature of the Christian West, I have said, present the heroic saga of the development of male subjectivity. It is not, however, the development of male subjectivity through and across female bodies that interests me. Nor is it the importance, even the centrality, of female figures to the male drama that I want to examine in the chapters to follow. In this book I want instead to explore one of the most fundamental figures by which human subjectivity has been represented in the literature and visual images of the Christian West, the naked body, and to examine the themes that dominate the different representation of male and female bodies. The gender-specific associations of representations of naked, and sometimes of "nude," bodies (we will examine this distinction shortly) with subjectivity—an inner life, a construction and cultivation of a "self "—will be the book's first agenda. I will then examine the use of female nakedness in the Christian West as a cipher for sin, sex, and death. The appropriation of the female body to represent male frustration and limitation in the societies of the Christian West has effectively precluded the formulation of a parallel representation of women's subjectivity. A historical woman who undertook to cultivate her own subjectivity necessarily incorporated the well-defined male scenario, understanding her body primarily as it appears in the male account and assimilating to her subjectivity the female figures of the male drama. One's relation to one's body—its needs and its pleasures—is not "natural" but, like subjectivity, is culturally mediated. For example, historians have long pondered why many medieval women practiced more extreme "mortification of the flesh" than did their male counterparts.40 Medieval women, as well as many women that came before and after them, designed their religious practices around introjected images of their own bodies as figures of sin, sex, and death. They then responded to these internalized figures with severe ascetic practices that produced not only a victory over these figurations of woman—in an increase of social esteem and social leverage—but often also illness and premature death. No one who uses representations of naked bodies as a primary resource can proceed very far without considering Kenneth Clark's famous distinction between "the naked and the nude." More than fifty years after his lecture was given at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., his analysis of the difference between nudity and nakedness continues to influence art historians and scholars. Clark described the naked body as "no more than a point of departure" for the nude:

In short, "to be naked is to be deprived of our clothes and the word implies some of the embarrassment which most of us feel in that condition." The word "nude," on the other hand, connotes no such image of a "huddled, defenseless body, but of a balanced prosperous and confident body: the body re-formed."42 The illustrations in the 1956 publication of The Naked and the Nude reveal the gender assumptions in Clark's argument. All the illustrations that appear on the pages from which I have quoted are of nude females. The "shapeless, pitiful model" from which art is created, then, appears to be female. The painter-spectator, on the other hand, the "we," is the critical male who eliminates the "small imperfections" and creates a body with ideal proportions. The social practice of professional painting also insisted on the painter's maleness, as academies in which figure drawing and painting from nude models were taught did not admit women until the end of the eighteenth century. All nudes need not, of course, be female in order to substantiate the point that the role of surveillance and interpretation of the naked figure is a male role; when a male model posed for a life study, he simply assumed the female role in relation to the painter. The naked body functions primarily as raw material for the artist: "It can be made expressive of a far wider and more civilizing experience." Furthermore, the naked body appropriated for recreation as a "nude" may contribute "associations," especially erotic associations, for the naked body, "is ourselves, and arouses memories of all the things we wish to do with ourselves; and first of all, we wish to perpetuate ourselves."43 Questions as to whose "civilizing experience" can be inscribed on the "shapeless, pitiful" body will probably arise in the mind of a reader who has followed my argument to this point. In Clark's distinction between "nakedness" and "nudity" the nude body is a representation of a naked body from which subjectivity, along with moles and lumps, has been elided. At the same moment when the naked body was "re-formed" to render it pleasingly balanced and proportioned and without blemishes, it lost its ability to express the personal character of the person whose body it is. "The transition from naked to nude," Annette Kuhn has written, "is also the transformation of woman into object."44 In Clark's description, the naked body becomes "a nude" by having its feeling ("embarrassment") removed along with the visible symbols of its individuality and personality ("wrinkles, pouches and other small imperfections"). The nude achieves universality at the expense of particularity. The subject of a nude painting has been deleted, replaced by the role the nude plays in representing "a far wider and more civilizing experience." In Clark's description of the classically proportioned nude, the religious meaning, or

meanings, of naked bodies has also disappeared. Not surprisingly, this is especially

evident in interpretations of the visual properties of female nudes. For Clark, "one

of the few classical canons of proportion of which we can be certain is that which, in a

female nude, took the same unit of measurement for the distance between the breasts, the

distance from the lower breast to the navel, and again from the navel to the division of

the legs."45 Eve's rounded and elongated belly might, for example, have represented—to the painter as well as to his immediate audience—the womb from which all humans were born. It might in addition have evoked her association with the Virgin Mary, the second Eve, from whose womb Christ took human flesh, an association strengthened by the exposure of Eve's left ear, in which, as legend has it, Mary conceived by the Holy Spirit. The ear, painted in greater detail than other parts of Eve's anatomy, as well as her small mouth and breasts—those "spheres" which Clark finds "distressingly small"—each contribute to a subordination of sensuality and sexuality that historical painters of nude subjects found necessary to ensure the communication of a primarily religious, rather than erotic, message. Memling's Eve is not, then, "nude," but naked. Her body, through its "small imperfections," reveals her religious significance as mother of all the living. Thus, "the nude—the reconstructed naked body—will not be as useful for my purposes as will representations in which the "naked" body is still evident, in which both subjectivity and religious meaning are expressed by the body. Even in depictions in which the author or painter intended to present a "re-formed" body, then, I will seek the contours of the other body, the body formed and informed by the life of the subject. In exploring representations of unclothed bodies in the Christian West, we must recognize religious meaning as an essential aspect of the cultivation of subjectivity. Christianity provided ideas and models for imagining a religious self, a self carefully cultivated in opposition to secular conditioning and socially prescribed roles. Moreover, Christianity has claimed to offer an alternative to secular values and conditioning without regard for race, gender, or social class. Examination of religious practices involving women and of religious representations of women reveals, however, a deeply gendered discourse, a discourse structured around assumptions of "natural" biological and social differences between men and women. Interestingly, in Christianity religious subjectivity seems, at first glance, to be structured similarly for men and women. Men are often encouraged to adopt behavior and attitudes commonly associated with women—humility, obedience, and sensitivity to the needs of others. And for women, "becoming male," as we will see in chapter 2, meant greater assertiveness, activity in public or semipublic spheres, resistance to social expectations, and "athletic" spiritual exercise. But the religious rhetoric that encouraged women to "become male" masked a fundamental inequality. In creating and cultivating a religious self, men retained their accustomed social privileges in new institutions—church and monastery—while women, in Christian institutions as in the society at large, did not choose their own roles or help to design the new institutions in accordance with their religious needs and insights. Thus, while Christianity appears to offer both men and women support and reward for religious commitment, women were generally prevented from creating social alternatives to match their religious commitment. Yet the limitation of women's social roles within Christianity conflicts with a religious rhetoric that explicitly acknowledged that women were capable of both rational thought and its corollary, religious subjectivity. From Augustine forward, Christian authors insisted that "inasmuch as woman was a human being, she certainly had a mind, and a rational mind, and therefore she was also made to the image of God." But Augustine qualified his affirmation, adding, "although on the physical side their sexual characteristics may suggest otherwise, namely, that man alone is said to be the image and glory of God.48 Between men and women, "there is no difference except in relation to the body, "49 But this difference was a large one. As Augustine's statement suggests, women's "nature" was determined by their physical difference from men, that is, by their bodies. Although women possess rationality, men's "nature" was determined by it.50 Thus, it seemed "reasonable" that human beings defined by mind should rule those defined by body. The "order of creation—man first, woman second—was understood to reflect cosmic order and to stipulate social order; female subordination was the linchpin of social order. In examining religious practices that pointedly engaged women's bodies and representations of female nakedness, I will bracket both theological discussions of women's rational capacities and "positive" images of good, nourishing, and socially valued women. I have done so, of course, for a reason—because, as so many Christian authors tell us, it was not women's minds that were problematic. Women's minds, they said, are "like" men's—perhaps not as fully developed, but still recognizably similar. The female body, however, was a problem for men; the control of female sexuality, reproduction, and economic labor was a perennial preoccupation and anxiety in the male-defined and -administered communities of the Christian West. Exploring social and religious practices and verbal and visual rhetoric surrounding female bodies, then, reveals not only men's concerns about women, but also features of the public environment in which women lived. This book seeks to clarify the religious themes by which, in the public sphere, women's bodies were dissociated from women as subjects and represented as figures in a male drama. By analyzing stylized depictions and descriptions of naked bodies in the Christian West, we can identify both an initially perplexing range of cultural and religious meanings of "the body" and analyze different treatments of male and female bodies. My resources for this study, then, are naked bodies as visualized and described in the art and literature of Western Christianity until about the seventeenth century, when religious meaning no longer provided the primary interpretive framework for depictions of nakedness. A study of practices and representations involving female nakedness will make evident an asymmetrical cultural interest in men and women as subjects in the Christian West. This is a study that must be undertaken, however, not in order to deplore the slender provision for women of symbols and images that incited, encouraged, and supported self-knowledge and the cultivation of a rich subjectivity, but in order to urge that, since the past cannot be changed, contemporary women's collaboration in creating art and literature that explores female subjectivity is all the more pressing. This project is, in fact, well underway in the last decades of the twentieth century. NOTES 1. Gayatri Spivak, quoted by Helena Michie, The Flesh Made Word: Female Figures and Women's Bodies (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 7. 2. Luce Irigaray, Speculum of the Other Woman, trans. Gillian C. Gill (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1974), 13. 3. Ibid., 133. 4. Susanne Kappeler, The Pornography of Representation (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 52-53. 5. Jacques Derrida, "Sending: On Representation," Social Research 49:2 (Summer 1982): 325. 6. The Epic of Gilgamesh, trans. N. K. Sanders (Baltimore: Penguin, 1960), 99. 7. "Siduri," however, means only "young woman." 8. Craig Owens, "The Discourse of Others: Feminists and Postmodernism," The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend, WA: Bay Press, 1983), 66. 9. Ibid., 57. 10. Ioan P. Culianu, Eros and Magic in the Renaissance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 5. 11. Culianu notes (ibid., 5) that "The sensus interior, inner sense, or Aristotelian common sense, which had become a concept inseparable not only from scholasticism but also from all western thought until the eighteenth century, is to keep its importance even for Descartes and reappear, perhaps for the last time, at the beginning of Kant's Critique of Pure Reason." 12. See also Augustine's description of phantasia and phantasma in The Literal Meaning of Genesis; CSEL 2, 128, n. 98, and 285, n. 100. 13. This is Hans-Georg Gadamer's term; see Truth and Method (New York: Crossroad, 1984). The "effective history" of an idea is the account of its interpretation and application in different social and intellectual contexts. 14. Culianu, Eros and Magic, 19. 15. Poeti del Duecento, ed. G. F. Contini (Milan and Naples, 1960), Vol. 1, 49; quoted by Culianu, 22. 16. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. J. H. Bernard (New York: Macmillan/Hafner, 1951), 37. 17. Ibid., 38. 18. Augustine, Enarrationes in Psalmos 132.10; trans. H. Chadwick, Augustine (London: Oxford University Press, 1986), 46. 19. Kappeler, Pornography of Representation, 55. 20. Francis Barker, The Tremulous Private Body: Essays on Subjection (New York: Methuen, 1984), 101. 21. See Craig Owens's discussion of classical, modern, and postmodern theories of representation in "Representation, Appropriation and Power," Art in America 70: 5 (May 1982): 9-21. 22. Owens, "Discourse," 66. 23. Ibid. 24. Jacques Derrida and others have advocated a distribution of the process of critical judgment, pointing out that socially located perspective always influences—and largely determines—critical judgments. See ibid., 58-59. 25. Ibid., 61. Though decentering or destabilizing the subject has been a project of postmodernism, it has been, according to Owens, "scandalously indifferent" to feminist critique of the masculine subject of representation. It is important to note, however, that destabilizing the subject is a project that can be undertaken only by those whose subjectivity is supported and privileged by existing social arrangements and institutions. It is a project for white, educated, male Westerners. Having no institutionalized subjectivity to decenter, women and minorities can deconstruct only the female or minority object constructed in male-designed and -administered societies. To identify the social location of a task, however, is not to devalue it or to diminish its significance. The importance of the destabilization of the subject in postmodern critical theory is that it indicates the awareness of at least a few men in positions of intellectual, institutional, and cultural leadership of the bankruptcy of the Western intellectual tradition. Modernism's part in this awareness was to formulate the claim to a universalizing mastery of reality by defining discourse in such a dramatic way that the blindness of such claims could become clear. 26. See also A Lexicon of St. Thomas Aquinas, vol. 1, ed. Roy J. Deferrari and Sister M. Inviolata Barry (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1948), 133; Lexique Philosophique de Guillaume D'Ockham; sapientia, scientia, ed. Leon Baudry (Paris: P. Lethielleux, 1958), 236-44; Latin Dictionary: carnalis, sapientia, scientia, ed. Lewis and Short (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1962), 293, 1629, 1642. 27. New Testament authors used the word "carnal" to emphasize the contrast between spiritual and material (2 Corinthians 10: 4; Romans 7:14; 1 Corinthians 3:3). Human nature under the domination of "lower" impulses was called "carnal." Like New Testament authors, patristic authors usually used "carnal" as a synonym for sin. As a technical theological term, however, "carnal" did not mean physical, nor was the human body necessarily devalued. Rather, the psyche was responsible for sin, using the body as a tool for the accomplishment of its agenda. 28. George Lakoff, Women, Fire, and Dangerous Things: What Categories Reveal about the Mind (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 7. 29. Tertullian, On the Resurrection of the Flesh xv; ANF 3, 555. 30. Subjectivity as a cultural artifact has been discussed by philosopher of science Rom Harré, who writes: "The fundamental reality is a conversation, effectively without beginning or end, to which, from time to time, individuals may make contributions. All that is personal in our mental and emotional lives is individually appropriated from the conversation going on around us and perhaps idiosyncratically transformed. The structure of our thinking and feeling will reflect, in various ways, the form and content of that conversation." Personal Being: A Theory for Individual Psychology (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 20. 31. Ruth Hubbard, "Constructing Sex Difference," New Literary History 19: 1 (Autumn 1987): 131. 32. Michele Montrelay, "Recherches sur la femininité," Critique 278 (July 1970). 33. Barker, Tremulous Private Body, 62-63; see also Michie, Flesh Made Word, passim. 34. Christine Buci-Glucksmann, "Catastrophic Utopia: The Feminine as Allegory of the Modern," in The Making of the Modern Body, ed. Catherine Gallagher and Thomas Laqueur (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 227. 35. Ellen Messer-Davidow, "The Philosophical Bases of Feminist Literary Criticism," New Literary History 19: 1 (Autumn 1987): 82. 36. Annette Kuhn, The Power of the Image: Essays on Representation and Sexuality (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1985), 96; also Griselda Pollock, "Women, Art, and Ideology: Questions for Feminist Art Historians," Women's Art Journal 4 (Spring/Summer 1983). 37. Messer-Davidow, "Philosophical Bases," 73. 38. Nancy Chodorow has written: "I argue that the sex/gender system is a social, psychological, and cultural totality. We cannot identify one sphere as uniquely causal or constructive of the others. You cannot understand the social organization of gender apart from the fact that we are all psychologically sexed and gendered, that we do not have a self apart from our being gendered." "Reply," in "On The Reproduction of Mothering: A Methodological Debate," Signs 6: 3 (Spring 1981): 502. 39. Ellen Messer-Davidow's article "The Philosophical Bases of Feminist Literary Criticism" outlines a method for identifying and exploring sex/gender systems. First, particularization specifies the individual voices from which statements and images originate; the cohesiveness of society is not assumed, but variables like gender and social location are critical to understanding the statement. Second, contextualization examines the culture in which the representation occurs. The relevant question here is: What cultural work did a particular representation do in its historical situation? The analyst should be on the alert for "structural congruence," the appearance of "the same sex/gender ideas in one instance of a medium (a novel), several instances of a medium (novels), or several instances of different media (novels, criticisms, manners, laws)." Metaphorical congruence, the repetition of the same metaphors across disciplinary discourses or media of representation, reveals the operation of rhetorical devices so grounded in cultural "common sense" that they can be counted on to move an argument or to persuade. Finally, influence can be traced in the circulation of ideas related to sex/gender from author to text and from reader-authors back to other authors and texts: "Discerning congruence and tracing influence are methods suited to analyze the middle ground of a complex system; they treat the entities and the relations that subsist among them. Enlarging these analyses synchronically and diachronically, and weaving in the variables of race, class, affectional preference, and other cultural specificities, feminist literary critics can approximate the sex/gender system" (87). 40. For a detailed discussion of the extreme food practices of medieval women, see Caroline Walker Bynum, Holy Fast and Holy Feast: The Religious Significance of Food to Medieval Women (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987). 41. Kenneth Clark, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Art (London: John Murray, 1956), 3, 4. 42. Ibid., 1. Compare Clark's unawareness of the male-gendered perspective that informs his evaluation of "Correggio's women," whom he calls "ravishing creatures" because "they have a self-surrender that has never been depicted elsewhere"; Feminine Beauty (New York: Rizzoli, 1980), 18. 43- Clark, The Nude, 6; Clark's equivocal use of "ourselves" in this sentence is revealing. The passive naked body that is recognized as "ourselves" and the spectator who feels an active wish to perpetuate "ourselves" are surely not the same person. 44. Kuhn, The Power of the Image, 11. 45. Clark, The Nude, 17. 46. Ibid., 18. 47. Ibid., 18-19. 48. Augustine, The Literal Meaning of Genesis 3.22; ACW 41, 99. 49. Ibid. 50. Even this limited but clear acknowledgment of women's rational capacities has not always been forthcoming. Though, admittedly, one cannot expect to find affirmation of women in the literature of witch persecution, the Malleus Maleficarum is especially emphatic on the issue of women's lack of rationality: "For, as regards intellect, or the understanding of spiritual things, [women] seem to be of a different nature than men. . . . Women are intellectually like children. . . . She is more carnal in nature than a man, as is clear from her many carnal abominations." The Malleus Maleficarum, trans. Montague Summers (New York: Dover, 1971), 44. |

For example, Albrecht

Dürer's Artist Drawing a Reclining Nude illustrates both the male artist's

distance from the female model and the asymmetrical relationship of the two. The

woman reclines, exposed and passive, positioned so that the artist's gaze moves from her

parted legs to her upper body. The artist, clothed and upright, uses grids, a sword, and

his calculating eye to reduce her body to lines on paper.

For example, Albrecht

Dürer's Artist Drawing a Reclining Nude illustrates both the male artist's

distance from the female model and the asymmetrical relationship of the two. The

woman reclines, exposed and passive, positioned so that the artist's gaze moves from her

parted legs to her upper body. The artist, clothed and upright, uses grids, a sword, and

his calculating eye to reduce her body to lines on paper. The

beauty of an "object" is thus not at all "objective," in the sense of

belonging to the object, but belongs entirely to the subject of the judgment; it is

"altogether referred to the subject and to its feeling of life."17

Kant's formula rephrases Augustine's statement of more than a thousand years before,

"Adam did not love Eve because she was beautiful; it was his love that made her

beautiful."18

The

beauty of an "object" is thus not at all "objective," in the sense of

belonging to the object, but belongs entirely to the subject of the judgment; it is

"altogether referred to the subject and to its feeling of life."17

Kant's formula rephrases Augustine's statement of more than a thousand years before,

"Adam did not love Eve because she was beautiful; it was his love that made her

beautiful."18 Using this

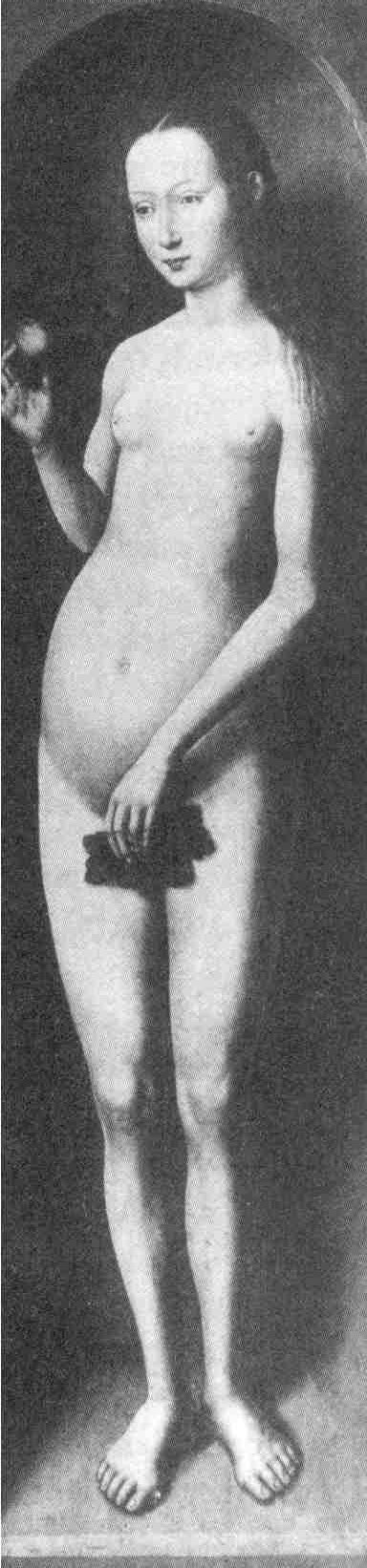

definition of accurate proportion, for example, he judges Hans Memling's nude Eve a

failure: "The basic pattern of the female body is still an oval, surmounted by two

spheres; but the oval has grown incredibly long, the spheres distressingly small. . . .

[In fact] the navel is exactly twice as far down the body as it is in the classical

scheme."46 Even if the artist's intent was to represent religious meaning

through Eve's body, Clark is certain that the painter intended to produce "a figure

which should conform to the ideal of his time, which should be the kind of shape which men

like to see."47

Using this

definition of accurate proportion, for example, he judges Hans Memling's nude Eve a

failure: "The basic pattern of the female body is still an oval, surmounted by two

spheres; but the oval has grown incredibly long, the spheres distressingly small. . . .

[In fact] the navel is exactly twice as far down the body as it is in the classical

scheme."46 Even if the artist's intent was to represent religious meaning

through Eve's body, Clark is certain that the painter intended to produce "a figure

which should conform to the ideal of his time, which should be the kind of shape which men

like to see."47